No se han encontrado productos.

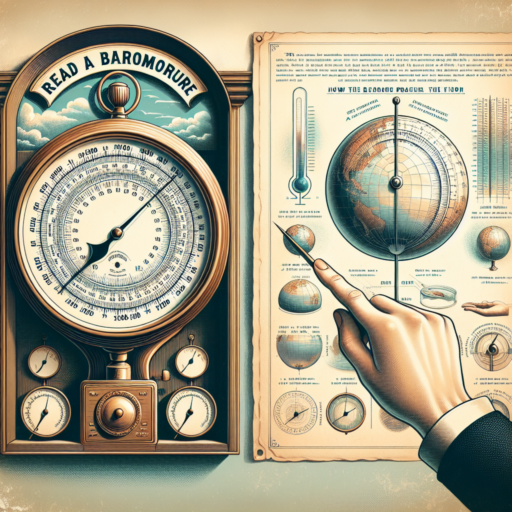

How do you read a barometer scale?

Reading a barometer scale is a fundamental skill for understanding atmospheric pressure and predicting weather changes. A barometer measures air pressure, and the scale is typically presented in inches of mercury (inHg) or millibars (hPa). When you look at a barometer, you will notice that it has a dial or a digital display that indicates the current air pressure.

Identifying Pressure Readings

The first step in reading a barometer scale is to identify where the pressure reading falls. If the scale is analog, a needle points to the current pressure value. For digital barometers, the pressure value is displayed on a screen. High pressure typically indicates clear weather, while low pressure suggests rain or stormy conditions. The standard atmospheric pressure at sea level is 29.92 inHg or 1013.25 hPa.

Monitoring Changes in Pressure

Understanding how to monitor changes in barometric pressure over time is crucial. This involves observing whether the pressure is rising, falling, or remaining stable. A rising barometer means improving weather conditions, whereas a falling barometer suggests deteriorating weather. Paying attention to the rate of pressure change can also provide insights. Rapid changes often indicate more significant weather events.

What do the numbers mean on a barometer?

Understanding the numbers on a barometer is crucial for interpreting atmospheric pressure and predicting weather changes. These numbers, measured in units such as millibars (mb), inches of mercury (inHg), or hectopascals (hPa), provide insights into the current state of the atmosphere around us. High readings typically signify fair, stable weather, while lower readings suggest poor weather conditions may be approaching.

A standard atmospheric pressure at sea level is defined as 1013.25 millibars (mb), 29.92 inches of mercury (inHg), or 1013.25 hectopascals (hPa). When the barometer’s numbers are higher than these standard values, it indicates high atmospheric pressure or anticyclonic conditions, often associated with clearer skies and calmer weather. Conversely, numbers lower than the standard values are indicative of low atmospheric pressure, which can lead to cloud formation, precipitation, and stormy weather. Understanding these numerical values is essential for weather forecasting and for anyone engaged in outdoor activities.

It’s worth noting that the interpretation of barometer readings can vary depending on geographical location and elevation. For instance, areas of high altitude will naturally have lower base readings on the barometer due to the thinner atmosphere. Adjusting the barometric readings according to the specific location helps in achieving more accurate weather predictions. Therefore, knowing how to read and interpret these numbers is not only fascinating but also a practical skill for daily life.

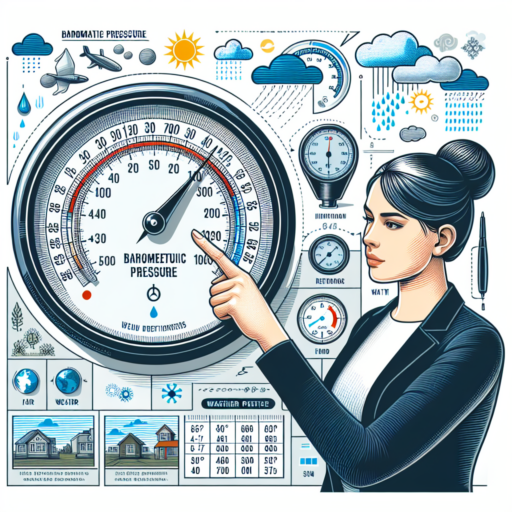

What is a barometer and how is it read?

A barometer is an essential tool used for measuring atmospheric pressure, a crucial component in weather forecasting. Primarily, it functions by responding to the changes in the weight of the air above it, enabling meteorologists and hobbyists alike to predict short-term weather changes. Understanding the mechanism behind a barometer’s operation is key to accurately reading and interpreting its measurements.

Types of Barometers

There are two main types of barometers commonly used today: mercury and aneroid. Mercury barometers use a glass tube filled with mercury, where the height of the mercury changes as atmospheric pressure varies. On the other hand, aneroid barometers employ a small, flexible metal box called an aneroid cell, which expands or contracts with changes in air pressure. Both types have their unique advantages and are selected based on the specific needs of the user.

Reading a Barometer

The process of reading a barometer varies slightly between the mercury and aneroid models. With mercury barometers, one must observe the level of the mercury in the tube, which is usually marked in inches or millimeters of mercury (Hg). A rising mercury level indicates high atmospheric pressure, suggesting clear skies and stable weather ahead. Conversely, falling mercury levels signal low pressure, which is often associated with bad weather conditions, such as storms and rain. Aneroid barometers, meanwhile, feature a dial gauge to display the pressure readings, making them relatively easier to read at a glance. Regardless of the type, regular calibration and interpretation of the readings in the context of recent weather patterns are essential for accurate forecasting.

What is a normal barometer reading?

Understanding the concept of a normal barometer reading is essential for anyone interested in meteorology or simply looking to get a sense of the upcoming weather. Barometric pressure, which is what a barometer measures, is often reported in inches of mercury (inHg) in the United States, and in millibars (mb) or hectopascals (hPa) in many other parts of the world. Generally, a «normal» barometer reading is considered to be around 29.92 inches of mercury (inHg) or 1013.25 millibars (mb)/hectopascals (hPa).

However, it’s important to recognize that what might be considered a «normal» reading can vary slightly depending on your geographical location. For example, at sea level, the average reading of 1013.25 mb/hPa is standard, but this can change at different altitudes. Areas situated at higher elevations will naturally have lower baseline pressures, making their «normal» somewhat different from that at sea level.

In the context of weather forecasting and analysis, knowing the local norm is crucial. A barometer reading that significantly deviates from the local average can indicate that changes in weather conditions are imminent. A reading that is higher than normal suggests clear and dry weather, while a reading that is significantly lower may indicate stormy weather ahead. This simplification, of course, assumes all other factors remain constant, which in meteorology, they rarely do.